Credit: MIT

Historically, anthrax (or B. anthracis)—a lethal bacterium that often manifests itself as spores, which can lie dormant for centuries—has basically been a blur of destruction and death. Prior to the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of people died every year from the disease; it wasn't until 1881 when Frenchman Louis Pasteur first developed a vaccine that we were spared its natural wrath.

But even in the wake of a proven treatment, the vast sterilization of raw animal waste, and sweeping anthrax eradication programs, we sorrow-loving humans decided to keep it around for the express purpose of biological warfare (because, of course).

Weaponization of anthrax has been successfully accomplished by at least five bioweapons programs—including the UK, Japan, Russia, Iraq and the good 'ol US of A. (Let us not forget about the anthrax bioterrorism in 2001; anthrax spores were sent though the U.S. post office, resulting in 22 infections and 5 deaths.)

All in all, it's not an uplifting aspect of the human experience.

That is, until today.

MIT scientists Bradley Pentelute, Xiaoli Liao and Amy Rabideau are bringing sexy back, rendering anthrax's toxin nontoxic, and cleverly using it as a platform to deliver antibody drugs into cells.

Here's How It Works

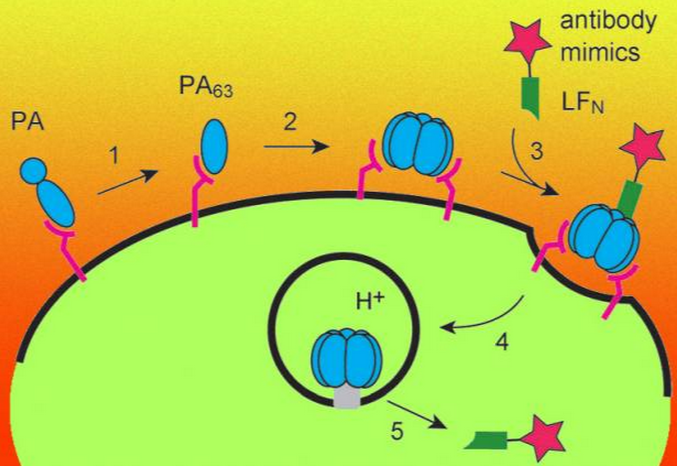

Anthrax possesses a protein called a protective antigen (PA), which binds to receptors called TEM8 and CMG2. (These are found on most mammalian cells.) This pesky PA attaches itself to another healthy cell and forms a docking site for two anthrax proteins called lethal factor (LF) and edema factor (EF). These proteins are then pumped into the cell through a narrow pore and go on to "disrupt cellular processes." That is, they murder the cell.

While antibodies—natural proteins the body produces to bind to foreign invaders—are an undeniably burgeoning area of pharmaceutical research and development, actualizing their potentiality has been hindered by the simple fact that it's damn difficult to get said proteins inside the cells. In short? Many cancer targets have remained "undruggable."

Says MIT scientist Pentelute:

“Crossing the cell membrane is really challenging. One of the major bottlenecks in biotechnology is that there really doesn’t exist a universal technology to deliver antibodies into cells.”

But rejoice! What the team discovered is that anthrax's slaughtering system could actually be rendered harmless by simply removing the sections of the LF and EF proteins that are responsible for their toxic activities—leaving behind the sections that allow the proteins to penetrate cells.

Pentelute and his team then replaced the toxic regions with "antibody mimics," enabling the antibodies to "catch a ride into cells" through the PA channel. Using these new methods, the MIT team was not only able to target Bcr-Abl (which causes chronic myeloid leukemia) but hRaf-1, a protein that is overactive in a wide variety of cancers.

Following their success, Pentelute has trotted out the whipping boys of science—mice of course!—and is poised to deliver "highly anticipated" findings in the coming months.